Let's Talk About Shipbuilding

Specifically, SECNAV, Shipyard Executives, and the Decision to Invest

This special edition of The Conservative Wahoo is in service to my work-based interest in the future of the Navy. For those of you who read for light-hearted social commentary (or dark political commentary) and who find the Navy stuff boring, please choose to do something other than reading this essay. For those interested in the Navy, it might be worth your while to stick around.

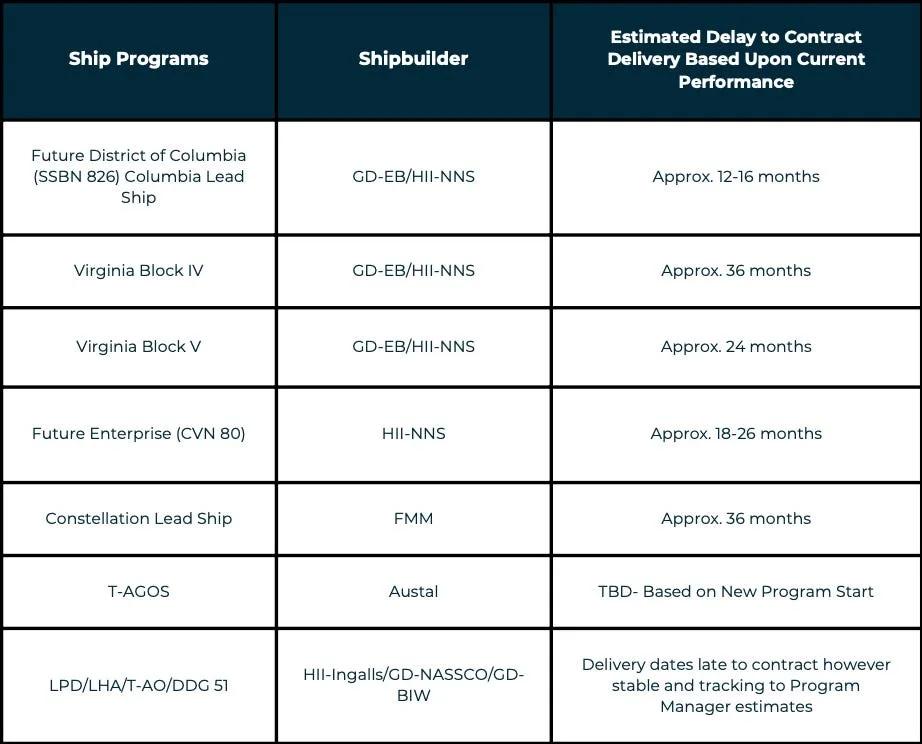

Our Secretary of the Navy has made news lately by publicly criticizing American shipyards for their failure to invest in capital improvements and workforce necessary to meet current (and future) demand. The plain truth is that the nation needs more ships, it needs them quickly, and our yards (collectively) are challenged to keep up with the demand, even as most of the Navy’s ongoing shipbuilding programs are behind schedule.

I have a number of opinions on this subject, some of which I shared publicly during a panel discussion at the recent Sea Air Space Symposium (see 42:00--44:06 below specifically:

Clearly, the Secretary of the Navy thinks that shipyard executives are not doing enough to invest in capacity increases the Navy needs to build the fleet it wants. The question then, is why aren’t they? Or more to the point, why didn't they 10 years ago, when doing so would have made a difference today? Given that they are in business to build quality warships at a fair price for a fair profit, why do we find ourselves in 2024 with a customer (Navy) who clearly wants to spend more money on ships, publicly criticizing shipyards for not doing enough to enable it.

The answer is time and money.

Time, in that for publicly traded corporations to responsibly invest in capital improvements necessary to increase capacity (after decades of shrinking), there must be a time horizon at which those investments are aimed. In a perfect world, the Navy would tell the shipyards how many ships they were going to build (and of which type) 7-10 years down the road, industry would invest (the money part) in plant and labor sufficient to meet these (in this case, increased) requirements, and everyone would be happy.

But we do not live in a perfect world.

We live in a world of annual (mostly) Navy-supplied 30 Year Shipbuilding Plans and annual (mostly) Congressional appropriations. A close analysis of these two events and how they interact over time reveals the challenging investment landscape the yards are being asked to participate in, especially publicly-held yards who must answer to shareholders interested in steady return.

30 Year Shipbuilding Plans

The Navy is required by statute to provide the Congress with an annual report on its shipbuilding programs for the subsequent 30 years. Ostensibly, this report is required to inform not only the Congress what the Navy’s intentions are, but also the shipbuilding industrial base. So the theory goes, this document provides the best available information about whether the Navy will grow, shrink, or remain about the same size over time. Furthermore (back to that perfect world again), where the plan indicates growth in future years, a responsive shipbuilding industrial base would make necessary internal investments to respond to that growth. Additionally, were the report to plan for contraction in numbers, one would expect that industrial base to also contract.

These investment decisions by publicly held American corporations are among the most scrutinized expenditures a shipyard can make, and Wall Street will punish a corporation that expends capital on improvements only to find that the government has changed its plans.

The question then—is does the government change its plans? In other words, over time—the time required to make capital investment decisions and then implement them—is there consistency in government signaling to industry through the 30 Year Plan, the kind of consistency that would buttress responsible investment decisions?

To investigate this question, I am indebted to the redoubtable Ron O’Rourke of the Congressional Research Service for the facts that I gathered into my (admittedly undergraduate) analysis here. Ron pumps out a number of informative reports a year, but his annual analysis of the Navy’s 30 Year Shipbuilding Plan is required reading, and is as anticipated a work as the actual plan itself. Here is the latest version of the report for 2024.

For the purposes of my analysis, I cadged two general pieces of Ron’s work. The first is a table that used to appear in his reports but that has been discontinued. It shows how the first 10 years of 30 year plans change over time. Here is an example from Ron’s 2018 analysis:

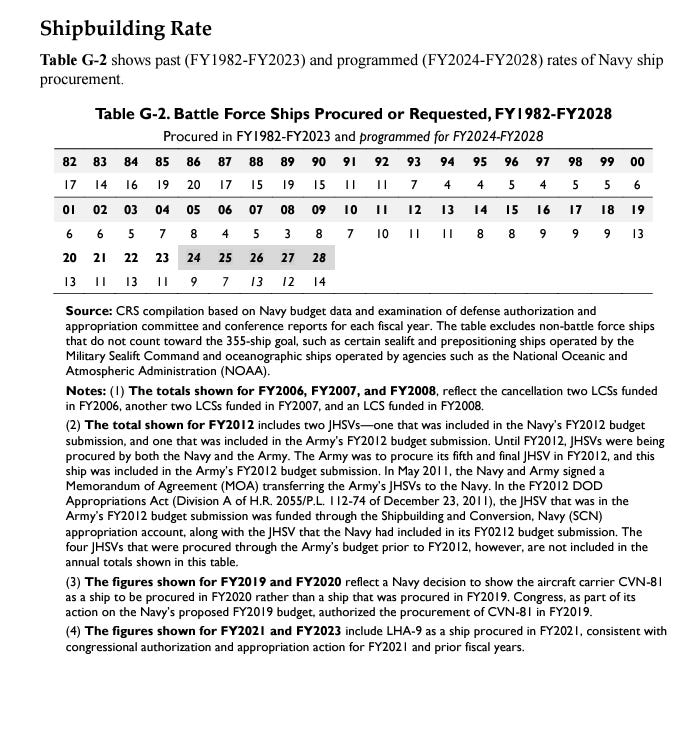

The second piece of data important to my thinking was to get a sense of how many ships ultimately had funds voted by Congress to purchase—a.k.a how many ships were “appropriated”. This is an important number, because it is the endpoint of a multi-year process involving Navy desires, Defense Department desires, White House desires, and Congressional desires. After years of “predicting” how many ships to buy in a given year (the signals sent to the shipbuilding industry), the proof is finally in the pudding, and the ships then get bought. Here is a roll-up of nearly forty years of how many ships actually got bought from O’Rourke’s latest report.

Throat Clearing

Before I dive into the big finish, let me stress a few things. First, rolling up a number of shipbuilding programs into one annual number of ships to be built is admittedly an imperfect means of measuring the Navy’s commitment to building ships. Not all ships are alike, and the procurement of some ships is simply more beneficial to the economy and workforce (not to mention national defense) than others. Additionally, individual corporations make their internal investment decisions not simply on a rolled up measure, but on the predicted numbers of ships that they are interested (or contracted to) in building. That said, the rolled up number of ships predicted to be built serves as a proxy for whether the Navy is growing or contracting, and that gross measure is important for investment decisions.

Additionally, variations and instability can impact a line of ships within a small number of years, creating considerable industrial churn. For instance, an entire class of amphibious warships was removed the 2023 and 2024 budget submissions (compared to the 2022 submission), and only to be re-inserted in the 2025 submission.

The Big Finish

Below is a graph that relates the data gleaned from Ron O’Rourke’s work.

Let us look at the year 2014, the first year under consideration. That year (green line) Congress bought 8 battle force ships. Over the previous ten years of 30 Year Shipbuilding Plan submissions, the Navy predicted at one point that 15 ships would be procured in 2014 (blue line) and at another point, it predicted that 7 ships (orange line) would be procured in 2014. Imagine being the Chief Financial Officer at Consolidated Shipbuilding Amalgamated on a shareholder call in the first quarter of 2005 answering an institutional investor’s inquiry about the wisdom of some capital improvements that the Board had approved based on Navy projections. All investing is a guess, even capital investments, but when the actual number of ships purchased ten years later is nearly the same number as the difference between the high and low, who would confidently invest?

Now look at the period from 2019-2022, where the number of ships Congress purchased was equal to or GREATER THAN the highest predicted number of ships in the previous ten years worth of 30 Year Plans. Let that sink in. Congress added ships to the total requested because they thought what was requested was insufficient. Look further at the orange line to see where the low predicted buy was in the previous ten years. Even if your corporate strategy for investment had been really fortunate and mapped out a capital investment approach appropriate to the average of the high and low, you’d STILL be behind the power curve of demand driven by a Congress dissatisfied with the Administration’s budgets.

The bottom line here is that there has been considerable instability over the years in the planned number of ships and the procured number of ships, and expecting an industry to invest against this volatility is unreasonable. Additionally, while this essay focuses mainly on the larger shipyards, the supplier base looks at the same volatility over time when making investment and hiring decisions, and the consequences of poor decisions are often felt with more immediacy at these levels.

What’s To Be Done?

Reduce the volatility.

As to how to do that, there is not much. The most effective “fix” in the short term is for the Navy to procure more (and more types of) ships under multi-year contracts. This is no panacea, as the country still “buys” them in annual appropriations, but were the Navy to exercise Congressionally granted authority to sign multi-year contracts, it would incur penalties payable to the shipyards in the event that ships contracted for are not procured. Put another way, there are incentives for the government to buy the ships it says it will buy, and THAT signal is far more important to CFO’s and shareholders than a 30 Year Shipbuilding Plan. To its credit, the Navy’s DDG multi-year buy and the possibility of a multi-year/multi-ship purchase of amphibious ships are steps in the right direction. Consideration should be given to bringing on a second shipbuilder for the FFG(X) program sooner rather than later and moving to multi-year contracts as soon as practicable.

Another angle would be for the President to talk about the Navy and the need for more ships and more people to work on ships and more shipyards and more people making parts for ships and more people providing services to people who make ships…you get the point. Perhaps a little more shipbuilding to go along with the high speed rail advocacy? My survey of American history tells me that every time the Navy has grown in our history—there was direct Presidential leadership involved. Every. Time. Congress really cannot do it on its own, or at least it hasn’t. Hell, my guess is that an inordinate number of jobs created in a pumped up shipbuilding industry would be “good, union” jobs, so maybe that will get Joe excited.

My final “what’s to be done” will ruffle some feathers of those who will dance around and say “Wahoo, you think you’re this great Conservative and you talk all the time about free markets, so how can you talk about industrial policy?” But I’m going to talk about industrial policy. You see, when it comes to national defense, I am in favor of our armed services PROTECTING free markets—not necessarily practicing them. The US Navy (specifically the Secretary and his Assistant Secretary for Research, Development, and Acquisition) need to sit down with the boys and girls on Capitol Hill and figure out how to treat the shipbuilding industrial base as a system, and then create/alter contract vehicles to enable systemic construction. The plain truth is that while there are labor shortages in some places, there is plenty of industrial labor in other places. We need to figure out how to more effectively match those two up. Machine shops, small yards, you name it—need to be brought into this mix in a way that meaningfully employs underused labor supply. Would this be hard to do? Yes. Would it be more expensive than what we do now? Yes. But what we do now needs to improve, and Winter is Coming.

Just refer to Adam Smith. "The first great exception to the principle of free trade is National Defense." Now how about an American Navigation Act?

I am a kindergarten student in this discussion, so let me ask a basic question. Isn't the problem that the U.S. has no viable shipbuilding industry that competes commercially? Wouldn't the problem of investing solely for national defense needs be lessened if we did? I would guess that there is a high level of commonality in shipyard facilities. Wouldn't a viable shipbuilding industry lessen the cost and probably reduce the timeframe?

If we are talking about industrial policy, is this a better target, or am I naive?