History

Section 8062(a) of USC Title 10 describes the composition and functions (often colloquially referred to as the “mission”) of the U.S. Navy thusly:

The Navy, within the Department of the Navy, includes, in general, naval combat and service forces and such aviation as may be organic therein. The Navy shall be organized, trained, and equipped primarily for prompt and sustained combat incident to operations at sea. It is responsible for the preparation of naval forces necessary for the effective prosecution of war except as otherwise assigned and, in accordance with integrated joint mobilization plans, for the expansion of the peacetime components of the Navy to meet the needs of war.

The important parts of this mission statement are “…primarily for prompt and sustained combat incident to operations at sea…” and “…responsible for the preparation of naval forces necessary for the effective prosecution of war…” The law of the land says the Navy is for “war” and for “combat”, and to anyone who has thought deeply about seapower and the role of the US Navy, these statements are unobjectionable. That they are unobjectionable however, does not mean they are complete. In fact, the mission stated above is not only mis-aligned with what the Navy is asked to do on a daily basis around the world, it is mis-aligned with what the Navy has been asked to do on a daily basis for the entire history of this Republic.

I first came into direct contact with the Title 10 mission of the Navy in 2006, when I was ordered to the Navy staff to lead what would turn into a twenty-month effort to develop a new “maritime strategy”. For those in the know, the Navy put together a now famous “maritime strategy” in the 1980’s under Navy Secretary John Lehman—a strategy based on exquisite intelligence about Soviet plans in a general war, and a plan that would “take the fight” to the Soviets in their near abroad and wherever else they happened to be. These were the Reagan years, and Lehman’s strategy was supercharged by the Reagan era military buildup. The US Navy that eventually reached some 594 ships in 1989 (the number is 290-ish today, headed to 280 if the FY 23 Biden Administration budget is any guide) was a powerful world-beater, the most powerful Navy the world had ever seen.

Seventeen years later when I was brought in to write strategy, the world had changed. The US was a “hyperpower”, peace had broken out everywhere, the War on Terror was the new great game, and otherwise smart people began to wonder just what it was we really needed a Navy for, or at least a Navy as large as the one we had. And while a post-Cold War dwindling of the fleet was not unexpected, the size of the Navy was dropping fast without a good story to justify even the force structure that existed. My team developed that good story. Known as “A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower”, our vision made a simple argument that appeared in the introduction, and I reproduce it here in its entirety:

The security, prosperity, and vital interests of the United States are increasingly coupled to those of other nations. Our Nation’s interests are best served by fostering a peaceful global system comprised of interdependent networks of trade, finance, information, law, people and governance. We prosper because of this system of exchange among nations, yet recognize it is vulnerable to a range of disruptions that can produce cascading and harmful effects far from their sources. Major power war, regional conflict, terrorism, lawlessness and natural disasters—all have the potential to threaten U.S. national security and world prosperity.

The oceans connect the nations of the world, even those countries that are landlocked. Because the maritime domain—the world’s oceans, seas, bays, estuaries, islands, coastal areas, littorals, and the airspace above them—supports 90% of the world’s trade, it carries the lifeblood of a global system that links every country on earth. Covering three-quarters of the planet, the oceans make neighbors of people around the world. They enable us to help friends in need and to confront and defeat aggression far from our shores.

Today, the United States and its partners find themselves competing for global influence in an era in which they are unlikely to be fully at war or fully at peace. Our challenge is to apply seapower in a manner that protects U.S. vital interests even as it promotes greater collective security, stability, and trust. While defending our homeland and defeating adversaries in war remain the indisputable ends of seapower, it must be applied more broadly if it is to serve the national interest.

This extended quotation is provided in order to contrast this vision with what you previously read in the Title 10 mission. Our 2006 strategy was designed to exert pressure upward, to make the case that while the Navy has critical and necessary wartime responsibilities and missions, it among elements of military power is UNIQUELY tasked with peacetime responsibilities, responsibilities that the Army and the Air Force did not share. As we were forming this strategy, we were again and again confronted with the Title 10 mission from above. War. Combat. Nothing about security and prosperity. Nothing about protection of a global system that was working to our benefit.

Not only was the mission statement in Title 10 misaligned with what the Navy was doing, it was acting to deny the Navy the resources it needed to do what it was being asked. Here in the mid-aughts of the 21st century, I began to become acquainted with one of the most interesting and long-running bureaucratic fights in the Pentagon, and that was the habitual recourse to the Title 10 mission statement—primarily by DoD, the Army, and the Air Force—in order to contest Navy budget requests. Because “war” and “combat” were the functions the Navy was legally required to do, bureaucrats reviews numbered war plans, the ships required to fill them, and the time those ships were required to be on station—and then questioned any and all force structure requests that exceeded this narrow formulation (with a fudge factor to account for maintenance and transit times). While there was some value affixed to the presence of combat forces forward, this value was constantly questioned and ripe for cutting. Navy people knew that those forces forward did a TON of things that were in the national security interests of the nation, but when the green eye-shade crowd held sway, pejoratives like “presence for presence sake” and “forward presence is a self-licking ice cream cone” would get thrown around, and then there was the bottom line buzz kill of “where can I find these things in Title 10”.

It is now 16 years after I began working on that strategy, and in the interim, I have made countless howls to the moon—both in and out of the Navy—that we needed to change Title 10 to more adequately account for what President after President has asked of the Navy for well-over two hundred years. Changing Title 10 would not add a single task to the Navy’s already overburdened list—it would simply legitimize it, and give the list greater standing in both budget crunches and times of plenty. Enter Congressman Mike Gallagher (R-WI)

Action

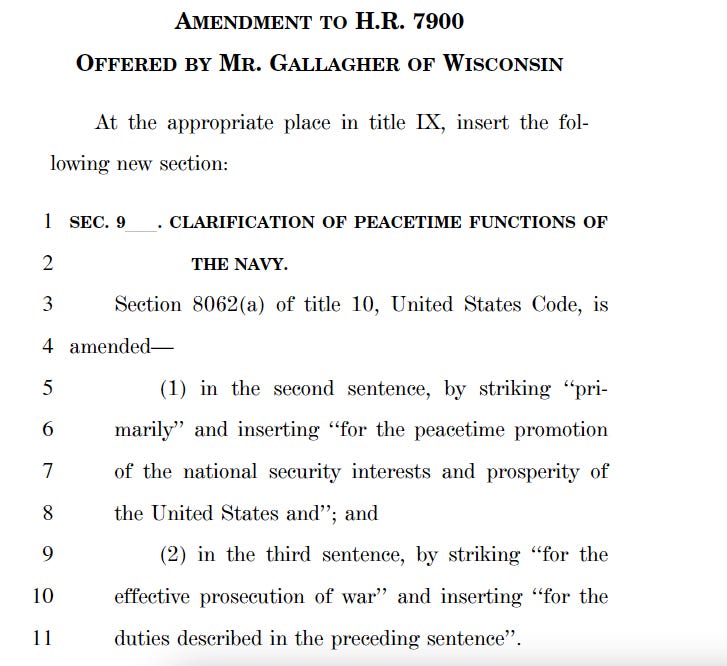

Gallagher is a Princeton grad, a PhD, a former Marine, and along with Rep. Elaine Luria (D-VA), among the most knowledgeable members of the House Armed Services Committee when it comes to American Seapower. Very few in that body care more about the Navy (and its land battery, the Marines) than Gallagher, and at some point, he must have looked at Title 10 and recognized the incongruence. But he does not have to howl at the moon, he is a Member of Congress and he can take action. Which he did, submitting an amendment to the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) that was passed by the HASC yesterday and which will now go to the floor for a full vote. Here is that amendment:

Cutting and pasting from the current Title 10 language, I come up with the following as the new Section 8062(a):

The Navy, within the Department of the Navy, includes, in general, naval combat and service forces and such aviation as may be organic therein. The Navy shall be organized, trained, and equipped for the peacetime promotion of the national security interests and prosperity of the United States and prompt and sustained combat incident to operations at sea. It is responsible for the preparation of naval forces necessary for the duties described in the preceding sentence except as otherwise assigned and, in accordance with integrated joint mobilization plans, for the expansion of the peacetime components of the Navy to meet the needs of war.

With very minor changes, the law of the land could very well come to reflect what we really want our Navy to do. This subtle change is however, tectonic. Because the peacetime value of the Navy is no longer negotiable, it cannot be minimized, or at least it cannot as easily be minimized. As I said earlier, this is NOT an increase in the Navy’s mission set, it is a codification of the Navy’s mission set. The Navy has been promoting the national security interests and prosperity of the United States in peacetime since its inception, but only now (if passed) will the law actually reflect this.

What’s Next

I am not an expert in legislative process, so discount this as you may. Presumably, when the NDAA is on the House floor, this amendment could be removed. If it is not, and the bill is passed, it will go to “conference” where the Senate Armed Services Committee’s NDAA bill would be reconciled with the House version. It could be removed there also. After that—when the reconciled NDAA goes back to the respective chambers—if the provision is in it, it would have to be voted on.

In the meantime, several things have to happen. DoD’s view on the amendment will be solicited by Capitol Hill, and the Navy (CNO and Secretary) are going to have to decide if they want to support it or not. I strongly recommend that they do, because without their support, OSD will almost certainly disagree with the change (and they may very well do so even with Navy support). OSD would likely be against this because it injects churn into the way they do business, unwanted churn. The other services are also unlikely to support it.

Seapower advocacy organizations (I’m looking at you, Navy League of the United States) need to get really busy, really fast in energizing the member base to call and email their representatives to voice support for this change. Navalists and those supporting a stronger Navy need to write and talk and hit social media hard on this. Inertia is a powerful thing. And winter is coming.

BZ